Introduction

This is the 4th installment in a series that examines data from the recently released 2013 BP Statistical Review of World Energy. The previous posts were:

- Renewable Energy Status Update 2013

- Hydropower and Geothermal Status Update 2013

- The State of Oil According to BP

Today’s post delves into the natural gas production picture.

The US as Gas King

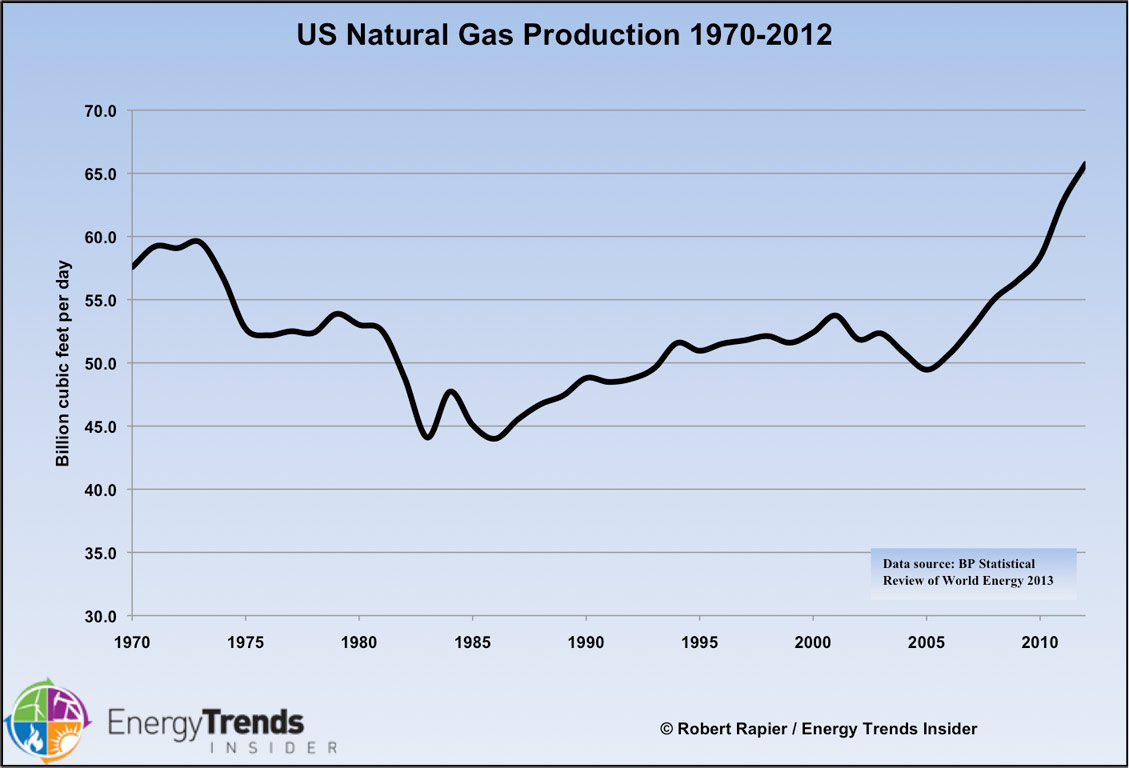

Over the past seven years, the US has firmly established itself as the global king of natural gas production (and consumption). In 2011, the US produced 62.7 billion cubic feet per day (bcfd) — more natural gas than any country had ever produced in a single year. That record fell in 2012 when the US produced 65.7 bcfd — which represented just over 20% of all the natural gas produced in the world. And thus far in 2013, US natural gas production is running ahead of 2012’s record production level.

The shift that has taken place since 2005 is amazing. It was in 2003 that the late Matt Simmons predicted, with “certainty,” that by 2005 the US would begin a long-term natural gas crisis for which the only solution was “to pray.” But Simmons had plenty of company in thinking that a natural gas crisis was imminent. In fact, it was widely believed that this would be the case, and companies began to make strategic acquisitions to cope with the expected shortfall.

Natural gas prices began to spike ever higher during 2005, and the Henry Hub Gulf Coast Natural Gas Spot Price crossed per million British thermal units (MMBTU) that December. That was also the month that my former employer ConocoPhillips (NYSE: COP) bought natural gas producer Burlington Resources for .6 billion. As a result of what would ultimately prove to be an ill-timed purchase, ConocoPhillips shares spent years underperforming those of competitors as natural gas production began to climb and depress prices.

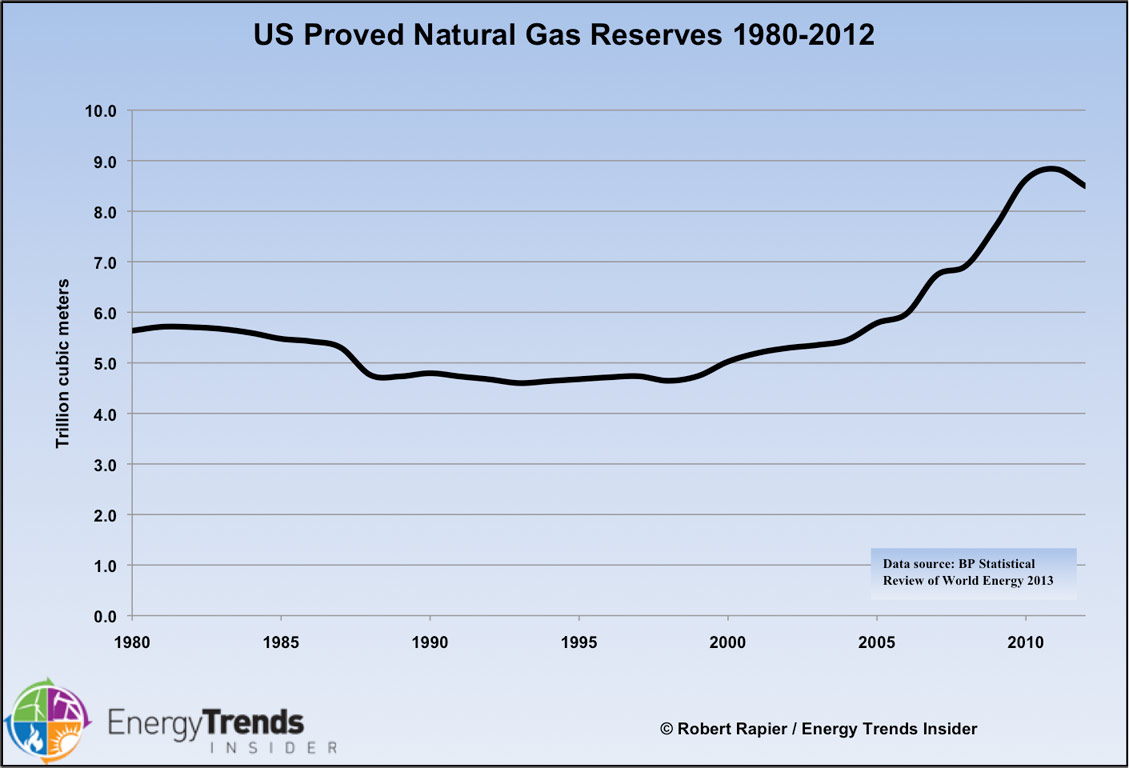

Since the low point in 2005, natural gas production in the US has risen every year (although proved reserves fell in 2012). In 2012, dry natural gas production was a full 33 percent higher than in 2005, with major implications for consumers and businesses alike.

The reason for this dramatic turnaround in US gas production was a combination of horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing. While fracking was first commercially introduced in the oil and gas industry in 1949, the combination with horizontal drilling is a more recent development that has boosted US gas reserves and production, and mobilized environmental opposition convinced that the practice will lead to polluted aquifers.

Consumers have benefited from the natural gas boom from lower heating and electricity bills, as many utilities have switched from coal to natural gas. In 2012 a paper from Yale estimated that in 2010 alone, when the spot price of natural gas averaged .37/MMBtu, lower natural gas prices were adding over 0 billion a year to the US economy. In 2012 the benefit was even greater as the average price slid all the way to .75/MMBtu. At the same time, the switch from coal to natural gas has been credited with helping to sharply reduce carbon dioxide emissions in the US.

The Global Picture

The global picture has mirrored that in the US, albeit to a lesser degree. Global gas production since 2005 is up almost 21%, while global gas reserves have risen by 19% over that time.

The global production situation will shift in coming years. While the US produces over 20% of the world’s natural gas, we have only 4.5% of the world’s proved natural gas reserves. The global leaders in proved natural gas reserves are Iran with 18%, followed by the Russian Federation (17.6%), and Qatar (13.4%). Altogether 43% of the world’s proved natural gas reserves are in the Middle East.

The Export Battle

Certain countries, such as Japan, are major importers of natural gas. US natural gas producers have begun eyeing these markets due to the large differential in price between US natural gas and LNG prices in certain countries. The cost of moving LNG from the US into foreign markets has been estimated at $6/MMBtu, and in 2012 the differential between US natural gas and LNG in Japan was $14/MMBtu. The differential between the US and European markets was above $8/MMBtu. These differentials provide a compelling economic case for LNG exports.

Cheniere Energy (NYSE: LNG) built a $2 billion LNG import facility just as US natural gas production took off and LNG imports began to plummet. Its share price followed suit, falling from $40 in 2007 to $1.12 by late 2008. But with US natural gas production surging, Cheniere decided to convert its Sabine Pass facility on the Louisiana/Texas border into an LNG export facility. It has received approval to do so from the Department of Energy, and given the current differential between US natural gas prices and LNG prices in other parts of the world, the terminal looks well-positioned to do brisk business. As a result, Cheniere’s share price has come back to the vicinity of $30.

The push to export LNG is pitting heavy natural gas consumers like Dow Chemical (NYSE: DOW) against natural gas producers like ExxonMobil. Like ConocoPhillips, ExxonMobil shares have underperformed in recent years because of the company’s ill-timed $41 billion buyout of natural gas producer XTO Energy in 2009 — when natural gas prices were around $6 per MMBtu. The acquisition of XTO made ExxonMobil the largest US natural gas producer, but in June 2012 then-CEO Rex Tillerson famously complained that “We are losing our shirts” on natural gas production because of low prices. LNG exports could change that equation.

Conclusions

LNG exports would probably cause higher domestic natural gas prices, hurting Dow and certain other heavy users of natural gas, as well as consumers. Regardless, expect more LNG licenses to be approved, and as long as natural gas production remains strong then natural gas producers in the US should benefit.

So investors can expect higher natural gas prices, but not a return to the lofty levels of 2005. As higher demand boosts prices, some of the natural-gas production shut-in during the recent slump will be brought back online, bolstering supply and limiting the price increases.

Source: Energy Trend Insider